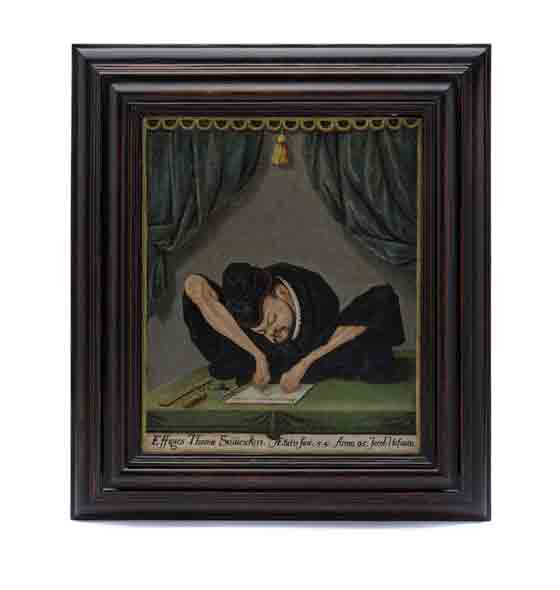

Thomas Schweicker, the ‘Wondrous Man of Schwäbisch Hall‘ from the

Dresden Kunstkammer

Jakob Hoffmann, signed

Schwäbisch Hall, dated 1595

Oil on canvas

Inscribed: ‘Effigies Thomae Schueickeri. Aetatis Suae, 54 Anno. 95. Jacob Hofman’ Royal Saxon seal on the reverse of the stretch frame: ‘KONIGL. SACHS GEMÄLDE GALLERIE’

Height 36.5 cm, width 30.5 cm

Provenance: In the Electoral Saxon Kunstkammer in the Dresden Residenz since 1603; mentioned in the Kunstkammer inventories drawn up in 1610, 1619, 1640 and 1741; since 1832 in the Royal Saxon Painting Gallery in Dresden; sold in the 19th century with other works from the Dresden Kunstkammer

Published in: Laue, G.: The ‘Wondrous Man of Schwäbisch Hall’ from the Dresden Kunstkammer, Kunstkammer Edition 8, Munich 2022

SOLD - Please contact us for similar artwork!

As the ‘Wondrous Man of Schwäbisch Hall’, Thomas Schweicker was one of the best-known celebrities of his time in the latter half of the 16th century. Born without arms and hands in Schwäbisch Hall in 1540, Schweicker had succeeded in overcoming the caprices of Nature that had presided over his birth by learning to use his legs and feet like arms and hands, and by doing so with such consummate skill that he became a calligrapher. His calligraphic works earned him the admiration of numerous distinguished figures from public life. Scholars and princes travelled to Schwäbisch Hall to pay homage personally to the artist who wrote with his feet – in hopes of acquiring one of his exquisitely executed calligraphic works because they were so highly prized among collectors as coveted treasures. The portrait painted in 1595 by Jakob Hoffmann of Hall features Schweicker as a wonder of Nature. A wax seal on the back of the wedge frame attests that this painting belonged to the inventory of the Royal Saxon Paintings Gallery in Dresden in the 19th century. In addition, archive records prove that by 1603 the painting was already in the Electoral Saxon Kunstkammer in the Dresden Residenz. In the Kunst- and Wunderkammer context, where man defined himself as an artist competing against divine or natural creative powers, Thomas Schweicker was considered the prime example of man’s creative potential. In a princely collection such as the Dresden Kunstkammer, portraits of the artist and his calligraphic works were further charged with symbolism in the sense of representatio majestatis: in analogy to the ‘art of governance’ they alluded to a territorial ruler’s ability to grasp the nature of his principality and his subjects, to deal with it and shape it in a beneficial way. In fact, the creative powers of the disabled artist were transferred in the princely collection room to the prince himself, who by the grace of God practiced the art of governance despite all the obstacles laid in his way by Nature, overcoming them with the same elegance and consummate artistry as the disabled artist who painted with his feet when executing calligraphy.