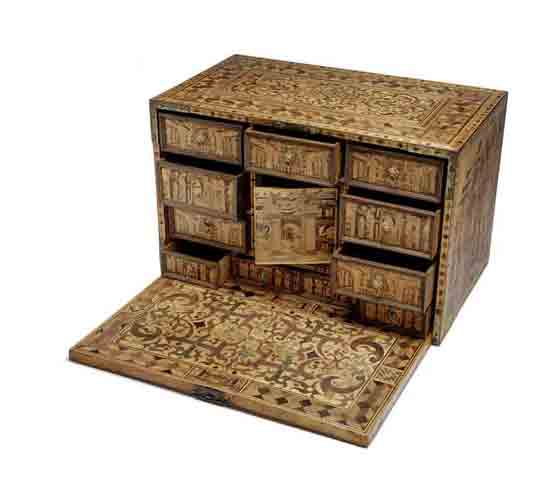

Perspective cabinet

Lienhart Strohmair, attr.

Augsburg, ca 1560

Native deciduous and fruitwoods in marquetry; mounts and fittings: etched and fire-gilded iron, fire-gilt brass

Height 44 cm, width 70 cm, depth 40 cm

Published in: Laue, G.: Der Madrider Kabinettschrank. Ein Augsburger Renaissace-Möbel für den spanischen Hof. The Madrid Cabinet. Renaissance Furniture from Augsburg for the Spanish Court, Kunstkammer Edition 6, Munich 2019, p. 58, Fig. 59

Cubic in form and structured as a fall-front chest, this magnificent “Schreibtisch” or “writing desk” belongs to the most elaborated collector’s cabinets created in Augsburg, the European capital of cabinetmaking, in the second half of the 16th century. It stands out through the refined inlaid veneer that depicts perspective vedutes of ruined building – a rare decorative scheme that rises two issues dear to Renaissance artists: the rules of linear perspective and the vanity of earthly life. Writing-cabinets with such sophisticated, inventive and precious marquetry are rare survivals indeed. Noteworthy in this connection are comparable Augsburg cabinets in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Museo Lázaro Galdiano in Madrid and Veltrusy Mansion near Prague. These cabinets are dated to ca 1560 on the basis of their exceptional decoration with perspective vedute and probably coming from the same Augsburg Kistler workshop. The Nuremberg and Munich ‘writing-desks’ are attributed to the celebrated Augsburg Kistler Lienhard Strohmaier, who was probably also the maker of the other objects forming this small group of works, including the present perspective cabinet. Paul von Stetten, the eighteenth-century historiographer who chronicled the decorative arts in his Gewerb- und Handwerks-Geschichte der Reichs-Stadt Augsburg (1779), reported that a great many cabinets were made in Augsburg in the sixteenth century with ‘architectural representations in perspective, which few cabinetmakers, however, contrived to do successfully’. The only pieces he accounted among the few ‘real works of art’ were the ‘cabinets made with great artistry’ by Bartholomäus Weishaupt and Lienhard Strohmair. Strohmair is recorded as having worked in Augsburg since 1538 and until he died in 1567. A documented quarrel with the Augsburg City Council proves that he had the largest cabinetmaker workshop in Augsburg and specialised in the finest furnishings that he sold not only to the Imperial court but also to foreign dignitaries.